The Complex Relationship and Looming Crisis Between Our Thirst For Water and Our Hunger for Energy

April 15th, 2015

Via Inter Press Service, a look at the tight watergy nexus in Brazil:

In Brazil water and electricity go together, and two years of scant rainfall have left tens of millions of people on the verge of water and power rationing, boosting arguments for the need to fight deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

Two-thirds of Brazil’s electricity comes from dammed rivers, whose water levels have dropped alarmingly. The crisis has triggered renewed concern over climate change and the need to reforest river banks, and has given rise to new debate about the country’s energy system.

“Energy sources must be diversified and we have to reduce dependency on hydroelectric stations and fossil fuel-powered thermoelectric plants, in order to deal with more and more frequent extreme climate events,” the vice president of the non-governmental Vitae Civilis Institute, Delcio Rodrigues, told Tierramérica.

Hydroelectricity accounted for nearly 90 percent of the country’s electric power until the 2001 “blackout”, which forced the authorities to adopt rationing measures for eight months. Since then, the more expensive and dirtier thermal power has grown, to create a more stable electricity supply.

Today, thermal plants, which are mainly fueled by oil, provide 28 percent of the country’s power, compared to the 66.3 percent that comes from hydroelectricity.

Advocates of hydropower call for a return to large dams, whose reservoirs have a capacity to weather lengthy droughts. The instability in supply is due, they argue, to the plants of the past, which could only retain water for a limited amount of time due to environmental regulations.

But “the biggest reservoir of water is forests,” said Rodrigues, explaining that without deforestation, which affects all watersheds, more water would be retained in the soil, which would keep levels up in the rivers.

“Forests are a source, means and end of water flows, because they produce continental atmospheric moisture and help rain infiltrate the soil, which accumulates water, and they protect reservoirs,” said climate researcher Antonio Donato Nobre.

“In the Amazon, 27 percent of the forest is affected by degradation and 20 percent by total clear-cutting,” said Nobre, with the Amazon Research Institute and the National Institute for Space Research.

That fuels forest fires. “Fires didn’t used to penetrate moist areas in the rainforest that were still green, but now they do; they advance into the forest, burning immense extensions of land,” he told Tierramérica.

“Trees in the Amazon aren´t tolerant of fire, unlike the ones in the Cerrado (wooded savannah) ecosystem, which have adapted to periodic fires. It takes the Amazon forests centuries to recover,” he said.

The scientist is worried that deforestation is affecting South America’s climate, even reducing rainfall in Southeast Brazil, the most populated part of the country, which generates the most hydroelectricity.

“Studies are needed to quantify the moisture transported to different watersheds, in order to assess the climate relationship between the Amazon and other regions,” he said.

But in the eastern Amazon region, where the destruction and degradation of the rainforest are concentrated, climate alterations are already visible, such as a drop in rainfall and a lengthening of the dry season, he noted.

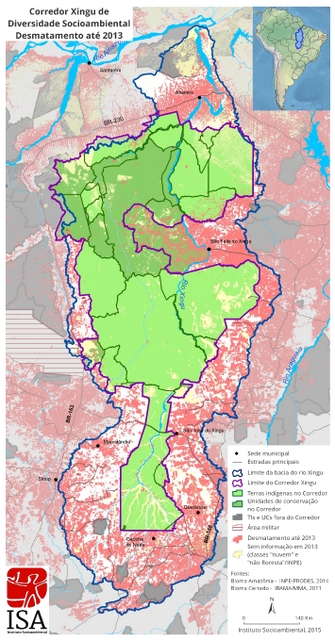

In the Xingú river basin this could be the year with the lowest precipitation levels in 14 years of measurements in the municipality of Canarana – where the headwaters lie – according to the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), which is carrying out a sustainability programme for indigenous people and riverbank dwellers in the river basin.

If that trend continues, it will affect the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant under construction 1,200 km downriver. With a capacity to generate 11,233 MW, it is to be the third-largest in the world once it comes onstream in 2019.

But the plant’s generation capacity could fall by nearly 40 percent by 2050, with respect to the projected total, if deforestation continues at the current pace, according to a study by eight Brazilian and U.S. researchers published in 2013 by the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States.

In 2013, deforestation in the Xingú river basin already reached 21 percent, the ISA estimated.

Other major hydropower dams under construction in the Amazon region could also suffer losses. In the Madeira River, torrential water flows in 2014 in tributaries in Bolivia and Peru submerged the area where the Jirau and Santo Antônio dams were built, affecting the operations of the plants, which had recently come onstream.

The tendency in the southern part of the Amazon basin is “more intense events, with more marked low and high water levels” such as the severe droughts of 2005 and 2010 and worse than usual flooding in 2009 and 2012, said Naziano Filizola, a hydrologist at the Federal University of Amazonas.

“Besides modifying water flows, deforestation is linked to agriculture, which dumps pesticides in the river, such as in the Xingú River, where indigenous people have noticed a reduction in water quality,” he told Tierramérica.

Hydroelectric construction projects fuel that process by drawing migrant workers from other parts of the country and abroad, expanding the local population without offering adequate conditions, he added.

Nevertheless, the most intense impact on the energy supply due to insufficient rainfall is now being seen in the Planalto Central highlands region, where the Cerrado is the predominant biome. The savannah ecosystem, where the main rivers tapped for hydropower rise, is the second-most extensive in Brazil, after the Amazon rainforest.

The Paraná River, which runs north to south and has the highest generating capacity in Brazil, receives half of its waters from the Cerrado. And in the case of the Tocantins River, which flows towards the northern Amazon region, that proportion is 60 percent, said Jorge Werneck, a researcher with the Brazilian government’s agricultural research agency, EMBRAPA.

Those two rivers drive the two biggest hydropower stations currently operating in Brazil: Itaipú, which is shared with Paraguay, and Tucuruí. Both are among the five largest in the world.

Another example is the São Francisco River, the main source of energy in the semiarid Northeast: 94 percent of its flow comes from the Cerrado.

In the area where he makes his field observations, around Brasilia, where several rivers have their headwaters, Werneck, a specialist in hydrology with EMBRAPA Cerrado, has seen a general tendency for the dry season to expand.

“But data and studies are needed to verify the link between deforestation in the Amazon and changes in the rainfall patterns in Brazil’s west-central and southeast regions,” he said.

In 2014 there was drought in both of these regions, which comprise most of the Cerrado, but “there was no lack of moisture in the Amazon – in fact it rained a lot in the states of Rondônia and Acre,” on the border with Bolivia and Peru, where there was heavy flooding, he said.

Forests provide a variety of ecological services, but it is not possible to assert that they produce and conserve water on a large scale, he said. The treetops “keep 25 percent of the rain from reaching the ground, and evapotranspiration reduces the amount of water that reaches the rivers, where we need it,” he added.

“Assessing the hydrology of forests remains a challenge,” he said.

But Nobre says large forests are “biotic bombs” that attract and produce rain. In his opinion, it is not enough to prevent deforestation in the Amazon; it is urgently necessary to reforest, in order to recuperate the rainforest’s climate services.

One example to follow is the Itaipú hydropower station, which reforested its area of direct influence in the Paraná River basin, revitalising the tributaries, through its programme “Cultivating good water”.

This entry was posted on Wednesday, April 15th, 2015 at 4:53 pm and is filed under Uncategorized. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Educated at Yale University (Bachelor of Arts - History) and Harvard (Master in Public Policy - International Development), Monty Simus has held a lifelong interest in environmental and conservation issues, primarily as they relate to freshwater scarcity, renewable energy, and national park policy. Working from a water-scarce base in Las Vegas with his wife and son, he is the founder of Water Politics, an organization dedicated to the identification and analysis of geopolitical water issues arising from the world’s growing and vast water deficits, and is also a co-founder of SmartMarkets, an eco-preneurial venture that applies web 2.0 technology and online social networking innovations to motivate energy & water conservation. He previously worked for an independent power producer in Central Asia; co-authored an article appearing in the Summer 2010 issue of the Tulane Environmental Law Journal, titled: “The Water Ethic: The Inexorable Birth Of A Certain Alienable Right”; and authored an article appearing in the inaugural issue of Johns Hopkins University's Global Water Magazine in July 2010 titled: “H2Own: The Water Ethic and an Equitable Market for the Exchange of Individual Water Efficiency Credits.”